Understanding Sensory Processing

We’ve all probably heard about someone having “sensory issues”, or maybe you've even said it yourself! But what does that really mean? Most people have sensory preferences — sounds or flavors or textures that they enjoy or avoid — but those preferences typically don’t interfere with daily life. For individuals with sensory processing issues, however, over- or under-responsiveness to sensory input can lead to mood swings, difficulty focusing, and behavioral challenges.

In this post, we’ll cover:

- The Seven Senses

- Sensory Processing Disorder

- Diagnosis and Help

- Sensory Budgets and Diets

- Putting It All Together

- Additional Resources

The Seven Senses

Most of us are familiar with five senses: sight, sound, touch, taste, and smell. But two additional, lesser-known senses also play a critical role in sensory processing:

- Proprioception (the “sixth sense”): This is the body’s ability to sense its own position in space. For example, being able to touch your nose with your eyes closed relies on proprioceptive input.

- Vestibular sense: This is responsible for balance and spatial orientation. It helps you walk up or down stairs without falling and plays a role in coordination.

All seven senses constantly send information to the brain to be processed and interpreted. This process helps regulate focus, emotional state, and physical response. When the brain struggles to manage this input efficiently — when there's too much or too little — it can lead to sensory dysregulation. This often manifests as anxiety, distraction, or behavioral reactions with no obvious external cause.

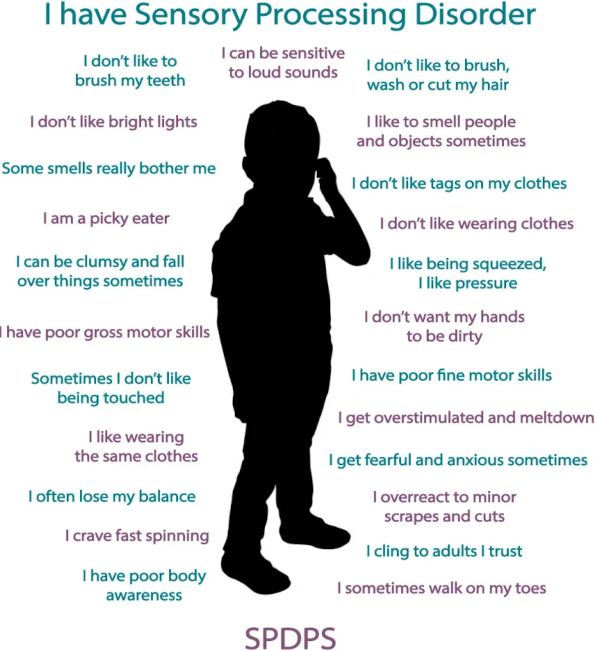

Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD)

Sensory Processing Disorder occurs when the brain has trouble receiving and responding appropriately to sensory input. It can present in two main forms:

- Oversensitivity (hypersensitivity): Everyday stimuli may feel overwhelming — like a tag in a shirt causing distress or loud noises triggering panic.

- Undersensitivity (hyposensitivity): A person may react to low levels of sensory input by actively seeking out intense stimulation — like constant spinning or crashing into things. Alternatively, someone experiencing undersensitivity may appear withdrawn or disinterested regardless of levels of stimulus.

SPD exists on a spectrum. For example:

- A child who dislikes the sound of a vacuum cleaner but can leave the room is showing a manageable response; one who melts down or vomits at the sound may need therapeutic support.

- A child who enjoys a merry-go-round is having fun; one who constantly spins may be seeking stronger sensory input to compensate for an under-responsive system.

- A child who is bored might amuse themselves by throwing their toys as a game; one who cannot handle quiet time and becomes destructive whenever expected to sit still may be expressing a fight response in response to sensory stress.

- A child might feel a bit shy or overwhelmed at a gathering with new people; a child who runs and hides from everyone at the family reunion may be experiencing a flight response to more sensory input than they can process.

- A child who clings to someone they know during a summer fireworks show is reacting as expected to new environment that is very loud and bright; a child who freezes in place or clings whenever they are in any new environment may be responding to unfamiliar stimuli with freeze or fawn responses.

Sensory processing disorder may affect only a single sense, or it can affect multiple senses. Most children react strongly to sensory triggers (such as the taste of a particular food or the texture of certain types of cloth) at times. Likewise, some children are unbothered by strong sensory inputs like loud environments when playing. But when these reactions (or lack thereof) become severe and disruptive enough to affect daily life, it’s time to seek help.

Overstimulation may cause a child to become overwhelmed, have a meltdown, or become hyperactive. Understimulation may appear as disinterest or a child not noticing things or may cause a child to seek out intense sensory experiences to compensate. Reactions may vary throughout the day, as the child’s environment and incoming sensory information vary, and as they become tired or hungry.

Not every strong response or lack of reaction to a particular sensory experience is SPD, but a pattern of disproportionate responses may be.

Diagnosis and Help

SPD is not yet a formally recognized diagnosis in all medical systems, but it is well understood and treated by occupational therapists (OTs) trained in sensory integration therapy. Not all OTs can provide sensory integration treatment — look for someone who offers both sensory processing and executive functioning therapies.

These professionals understand and can diagnose sensory processing disorder. They collaborate with the patient to assess their sensory thresholds, develop individual coping strategies, and create a plan tailored to the individual. Sensory integration therapy provides personalized tools and activities that the patient can use to manage their own sensory comfort levels. There is no one-size-fits-all approach; each toolkit is tailored to the individual’s needs, routines, and environments.

Sensory Budgets and Sensory Diets

- Sensory Budget: A sensory budget helps individuals balance the types and amounts of sensory input they encounter throughout their day – such as lighting, noise, or textures. It focuses on modifying environments—like reducing harsh lighting or using noise-canceling headphones—to manage sensory load.

- Sensory Diet: Despite the name, this has nothing to do with food. A sensory diet is a personalized set of activities or tools designed to provide the right sensory input at the right times. This might include movement breaks, fidget tools, deep pressure activities, or calming routines. A sensory diet usually includes routines that help provide stable and calming sensory input throughout the day, to help maintain a stabilizing sensory baseline. In addition, a sensory diet often includes specific tools to address unexpected stimuli, giving the individual ways to self-manage disruptive experiences.

The goal of both tools is to promote self-regulation by helping individuals stay within their optimal zone of sensory comfort by controlling and supplementing their incoming sensory experiences.

Putting it All Together

Diagnosing SPD and then creating a sensory budget and diet involves collaboration between the therapist, the individual (and often family or caregivers). The process includes:

- Identifying sensory triggers and tolerances

- Structured exposure to test responses

- Exploring reactions to specific items and activities

- Selecting calming or stimulating activities as needed

- Building a “sensory toolkit” for daily life

With the right support, individuals with SPD can learn to manage their own sensory needs, leading to improved focus, greater emotional balance, and more opportunity to participate in daily living activities.

Additional Resources

Understood – What is a Sensory Diet?

Autism Awareness Centre – What is a Sensory Diet?